Newspapers are still profitable, even in the midst of the most punishing ad drought in memory. Readership is at record levels, despite price hikes imposed by publishers. And web interlopers haven’t laid a glove on the industry’s status as society’s dominant news-gatherer.

In the latest sign of the industry’s strength, Statscan reported this week that the pretax profit margin for Canadian newspapers averaged 9.9 per cent last year. That’s down markedly from the halcyon pre-Internet, pre-ad-slump of 12.3 per cent in 2008. But it’s a long way from the extinction forecast for the industry by the most exuberant heralds of a purely digital world, a brave new world devoid of household names like the New York Times, Le Monde and metro dailies like The Toronto Star.

As recently as last year, the industry was shuddering from 2009’s stomach-churning plunge in advertising revenues, which cratered after the onset of the global financial crisis. Sam Zell, the real estate mogul who had just bought newspaper conglomerate Tribune Co., moaned that the industry was “looking at some of the worst advertising numbers in the history of the world.”

In the darkest hours, the venerable Seattle Post-Intelligencer and Denver’s Rocky Mountain News closed. Tribune and CanWest Global Communications Corp., the largest newspaper owners in the U.S. and Canada, respectively, filed for bankruptcy protection.

Yet newspapers appear poised for a bright future. To be sure, ad-revenue growth remains anaemic. And the industry has likely lost forever its lucrative franchise in classified ads, to Craigslist and other online upstarts.

But the widely anticipated “hollowing out” of newspaper readership hasn’t happened. Quite the opposite. The newspaper habit is stronger than ever, with more than three-quarters of Canadian adults, or 77 per cent, reading the print or online edition of a paper at least once a week.

Over the past five years, readership of Canada’s 95 dailies has actually increased, albeit by a modest 3.7 per cent. More than 14.7 million Canadians read a paper each week. That’s a “reach,” or portion of potential audience, that no non-traditional medium comes close to matching.

As important, Canadians are spending more time with newspapers. According to the latest, 2009-10, readership survey by NADbank, the industry group, in Canada’s top 10 markets readers are spending more than 3.8 hours a week with newspaper print editions. That’s up 2.1 per cent over the past three years.

And that at a time when publishers were raising the price of their product, enabling the industry to post a 12.9 per cent increase in circulation revenue between 2007 and 2009 to cushion a 4.9 per cent drop in ad revenues.

Meanwhile, readers are not spending close to two hours a week with the online editions of newspapers. Traditional papers are winning out in cyberspace. Retaining their status as the most trusted of news sources, with brand names dating back to 1778 in the case of the Montreal Gazette, newspapers have been able to build huge online audiences from scratch. The New York Times now claims a staggering 55 million online readers, against a weekday print circulation of less than 900,000. Online now accounts for 26 per cent of the New York Times’ total ad revenue.

Newspapers have benefited enormously from the rapid fragmentation of cyberspace.

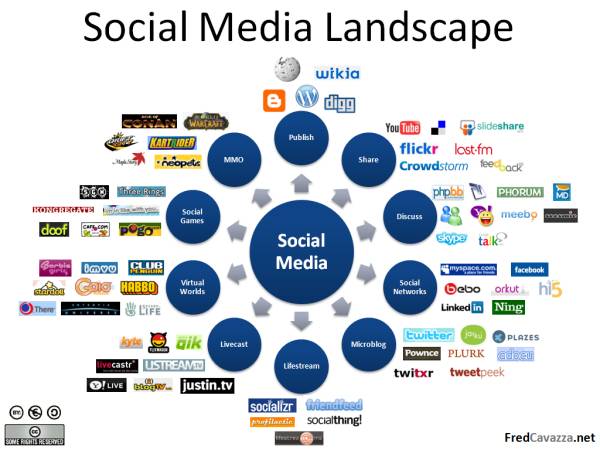

The online world now is populated by social-networking sites, including Facebook with its 555 million members. There are some 200 million “blogs,” or personal web logs of writers on every topic from orchids to T-bill investing. There are tens of thousands of specialized newsletters, some published by the usual financial-services industry suspects, others independent, but none differing in content from their non-pixel predecessors. Not to overlook the so-called “aggregators” that merely repackage the online content of traditional media sources.

In that hyper-crowded arena, the advantage has gone to the most familiar tribunes. That would include the 164-year-old Chicago Tribune, which like almost every daily in North America has continued to earn profits through the industry’s worst hours. Indeed, industry warhorses the New York Times, Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal and even Tribune have reported profit gains in the past year.

Having not endured a crisis of this order since Gutenberg, the industry took on the appearance of a man with his hair on fire and trying to put it out with a hammer. Yet the demise of the Seattle P-I and the “Rocky” were simply a long-delayed capitulation to the one-newspaper monopoly that has characterized U.S. cities since the 1970s. And Tribune and CanWest succumbed to unsustainable, acquisition-related debt.

The “barriers to entry,” in econospeak, for launching an online publication are exceedingly minimal. Anyone with a Facebook, Blogger or Flickr account can become a publisher. Volatility is the norm, as underfunded websites are routinely abandoned.

By contrast, Star owner Torstar Corp., with close to $1.5 billion in 2009 revenues, has the resources to launch a portfolio of websites, host dozens of bloggers, and maintain a costly IT crew to run a complex digital enterprise.

Which explains why top-flight U.S. bloggers Andrew Sullivan, Felix Salmon and Eric Alterman have given up their garrets to bunk in with the venerable Atlantic, Reuters and The Nation, respectively. And why aggregators Huffington Post and The Daily Beast have sought shelter in larger and more familiar enterprises, AOL Inc. and the 77-year-old Newsweek, respectively.

In the past 12 months, shares in North America’s top10 publicly traded newspaper firms have gained an average of 20.8 per cent. And that’s before any meaningful recovery in ad revenues, or significant migration of print advertisers to online. And ahead of the New York Times’ second experiment, later this year, with trying to charge for selected online content. That’s a feat the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times have pulled off, and that Murdoch’s general-interest papers are now attempting.

Not long into the Internet’s brief history, users were complaining that “trying to get a drink from the Web is like sipping from a fire hydrant.” That growing flood of information is a boon to traditional newspapers. They alone have the expertise to quickly collect and verify staggering amounts of data and present it in reader-friendly formats.

We’ll hear soon enough about the phoenix-like rebirth of newspapers. It will be a crock, since there were no ashes to rise from. But editors will enjoy handling those reports far more than the industry obits they’ve edited these past few years.

Between 2011 and 2015, revenue from digital advertising in the United States is expected to grow by 40% and to overtake all other platforms by 2016.

Between 2011 and 2015, revenue from digital advertising in the United States is expected to grow by 40% and to overtake all other platforms by 2016.